Why – What – Where – When

Why?

When you train many months for a big event, as I did for the Marmotte in July 2022, and then finally do it, although there may be a great sense of achievement — it all depends on how it went — there is inevitably a very flat period afterwards.

You are what the French call déboussolé: “boussole” is the French word for compass (in the sense of that little magnetic direction-finder, not the pointy, hinged thing-gee you used to stab yourself with accidentally in math and drafting class). You’ve lost your compass, your sense of direction, as the thing you are aiming for is now behind you. There is nothing in front. You’re left with the question,

Compass – the painless kind

What next?

What?

In the previous two years, my big event was in August, so the “what next?” period ahead of me was relatively short, before the cold of autumn and winter closed in, and the answer to the “what next?” question was a simple: “survive the winter”. So I just accepted it. This year, the big event was in early July, and afterwards, I decided to re-find my compass, rather than accept a long period in the doldrums.

I set my heart on the Tour du Mont Blanc.

To the best of my knowledge, there is not really an official route, all you have to do is find a path that covers the 360° of some rough-hewn circle, which has Mont Blanc more or less at its centre. As such circles are (in pre-computer days, anyway) drawn with a compass (this time, the pointy, hinged thing-gee), it seemed a sort of apt way to become “réboussolé”.

Compass – the painful kind.

So, as I say, I set my heart on it. I would do the Tour du Mont Blanc.

Where?

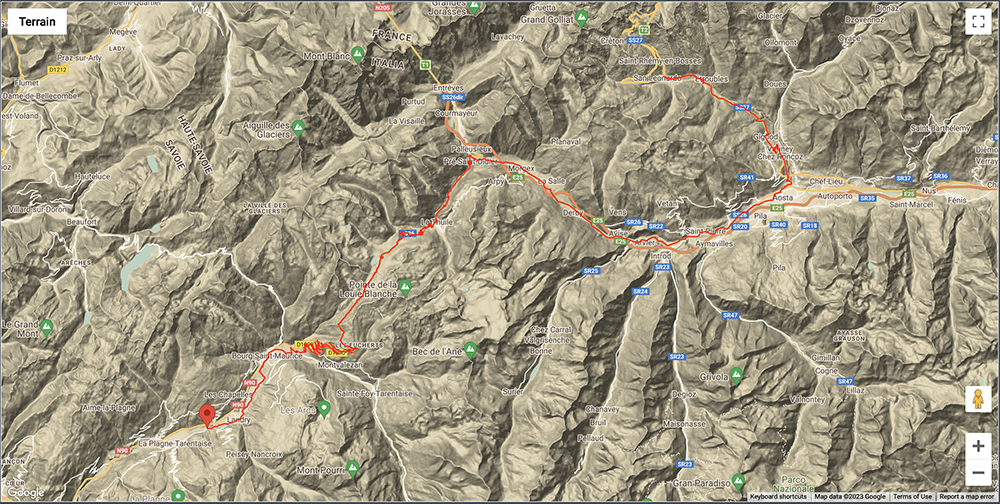

After some research, I decided on the following route:

Day 1: Home; Bourg-Saint-Maurice; Col du Petit Saint Bernard; Pré-Saint-Didier (despite the French-sounding name, in Italy); Aoste; Saint-Rhémy (a small village part way up the route to the Col du Grand Saint Bernard).

Day 2: Saint-Rhémy; Col du Grand Saint Bernard; Bourg-Saint-Pierre (Switzerland); Martigny; Chamonix (back in France).

Day 3: Chamonix; Saint Gervais; Mejève; Col des Saisies; Beaufort; Cormet de Roselend; Bourg-Saint-Maurice; Home.

When?

“When” was a pretty easy: there was no way I was going to leave during the holiday season, as there are a fair number of busy roads on the route, and a lot of dangerous inexperienced mountain drivers, tourists from flatter parts of France and other countries. So, sometime after the first weekend in September. As I have a pretty flexible work schedule (lots to do, but I can do it when I want), I could wait for the first good weather window. But I didn’t want to leave it too late: it would get cold. I regularly checked room availability in Saint-Rhémy, so I wouldn’t have to book, as I was unsure when and whether I would arrive. There always seemed to be several options, so I felt I would have no trouble finding a place on the day. The operative word there is “seemed”.

In the end, the stars aligned for the third week in September, I dropped the dog off at the kennel on the Sunday evening, and was busy pedalling, at very first light, Monday the 19th.

Day 1: Trouble in Etroubles

The sky was brilliantly clear when I left home, and the brightest stars were still visible. It was cold, about 4°C at the house, and colder yet when I got down to the road that parallels the Isère. I knew it would be at least an hour before I was up into the sunshine on the climb to the Col du Petit Saint Bernard. The first 10km or so are on a very slightly rising grade, and in order to work hard enough to keep my body warm, I had to cycle fast enough to freeze my toes and fingers. This was to be a leitmotif of the trip – agreeable warmth in some part of my body, aggravating cold elsewhere. It worried me to think how cold I would be on the descents: not much warming pedalling to do, and lots of cold wind at my face.

When I broke into the sunshine, it was brilliant. Although it came up from behind the mountains, the sun was still low in the sky, and so cast that very warm colour that you often see early on autumn days. Instant warming. It was fantastic.

Les Arcs.

On the col it was about 6°C, but the first bit of descent is a comparatively straight, and I was able to pedal to keep warm. But eventually the road descends into the forest, is in the shade, and becomes narrow through a series of closely-spaced switchbacks. I just could not pedal any longer, and so got cold in my entirety. Colder than the proverbial “frog in a pool”. Colder than the proverbial “Eskimo’s tool”.

How cold? Well, as I said in a text message to friends, I haven’t been that size or shape since I was a baby.

But of course losing altitude typically increases temperature, and I broke into the sunshine once again, several kilometres above les Tuilles. I stopped for a while to warm myself, and ensure I hadn’t frozen off any quasi-important parts of my anatomy. And I popped into the local tourist office, to confirm availability of rooms in Saint-Rhémy.

The woman was incredibly helpful, but was the bearer of pretty bad news. The French phrase I was taking to mean “more than one room like this available” in fact meant “no rooms like this available” (yes, after over a quarter of a century in France, I am still capable of making stupid mistakes like that). There was not a single hotel open in Saint Rhémy, and nothing much on the entire route above Aoste.

This was a huge blow to my plans. I was sure the Grand Saint Bernard (where I certainly could have stayed at the monastery) was an impossible effort, a climb too far, quite simply out of my range. On the other hand, if I stayed in Aoste, the second day of the trip would become ginormous, if I were still to hit Chamonix at the end of Day 2, as planned.

But the woman in the tourist office showed terrier-like persistence, and eventually she found a place for me at a campsite, in a kind of glorified garden shed, a sort of modern Hobbit-hovel. It would have to do.

Then down via a fast and brilliant descent to Pré-Saint-Didier.

Mini-Interlude

The whole of the Italian side of the Petit Saint Bernard col is a curious place. The people all speak Italian, but the place-names are all in French. One day I will do the research to understand why. But there is an uncanny sense that the whole region is in a kind of cultural time warp, where normal things are not quite what they seem.

In passing quickly, you can blunder through and never notice; or more slowly, you can catch your foot on some small cultural pebble, and realise you are in fact the stranger in an even stranger land.

I had to refuel in Pré-Saint Didier, and did so in the local shop. There I caught my foot on a small cultural pebble…

Superficially, the town itself has fully embraced the 21st century; the old buildings have been lovingly restored, but those ancient-modern facades are indeed facades, because the people behind them remain the same as they have over the centuries.

And so it was in the local shop. The frontispiece was beautifully, recently re-sculpted local stone; what (or whom) I found inside was hardly recent, and hardly re-sculpted.

The delicatessen part of the shop was at the very back, and behind the glass counter, which sported a range of hams and patés, cheeses, salads and olives in brine, held domain an ancient man (and so about 5 years older than me), balding, white hair at the sides of his head, sporting a pair of ferret eyes, pretty much challenging me to order something he could not deliver. As he seemed to be a man of no small resource, I took the simplest route, and asked for a ham sandwich.

I expected him to be disappointed by this choice, but instead he looked at me with renewed respect, as if a ham sandwich was the choice of a king, and in ordering it, I had proved my pedigree. It was demanded of me that I select which kind of ham. Although I chose the cheapest, he nodded in agreement, as though my choice represented the pinnacle of good taste. In my answer, “yes, I would have cheese”, he laid his finger against the side of his nose, as though the response was particularly sagacious on my part. And on and on, in such ways, he crafted the most mundane of ham sandwiches, but which to him (and so to me, because his enthusiasm was infectious) seemed indeed the pinnacle – never mind just ham sandwiches or good taste – of culinary art.

And you know, because of him it was. When I finally got my teeth into it, that dull bit of bread, meat and cheese really was the ham sandwich of the century…

The Continued Descent

By this time, temperatures were fully in my comfort zone, the road dead straight in descent, and I set a blistering pace (50+ km/hr most of the way) to Aoste. Let the climbing begin.

I will admit the transition was difficult. I think the cold as much as anything had drained me, and I struggled to find a pace that felt comfortable. When I finally did, it was at a wattage well below my target, and I alternated between accepting it, and forcing myself to go faster. Eventually the former instinct won out.

When I arrived at Saint-Rhémy, I called the campsite to get final directions. Like some kind of cruel but real joke, the woman informed me I’d gone too far, and I had to descend 300 metres altitude back to the now seemingly aptly named Etroubles. Trouble in Etroubles. I was able to laugh at that, and in fact the descent was a lot of fun. When I arrived at the campsite, the Hobbit-hovel was agreeably Hobbit-esque, the shower hot, the pizzeria pizza not all that bad, in bed the abandonment into what I think Mann once called “the vegetative state” so completely and utterly necessary, that I didn’t care: the day was done.

The Hobbit Hovel

Day 1 was done.

Day 1 Route

Day 2: From Cold to Col to Cold to Col to Col

I wanted to be away at very first light, as this was meant to be the biggest day of the trip. The campsite staff were agreeably obliging, checking me out a half an hour earlier than was normal for them, and with just enough light to find my way, I set off.

The disadvantage of an early start is there is no sun to provide warmth; the advantage, is that when the sun does finally arrive, it doubles as both a source of heat and inspiration. I’d never been on a bike before in sub-zero temperatures, but I found them about an hour into the day, on the climb to the Grand Saint Bernard. Given I was climbing, it was not so bad.

But it was bloody cold.

Just above 0ºC.

There was a bit of traffic even that early, but I knew all the cars would be heading for the near 6km long tunnel that passes under the col. Once I hit the bifurcation where it splits towards the tunnel or the col, the road was mine and mine alone. I broke into the sun about an hour into the day, and negotiated a series of switchbacks on my way up to the col at 2,469m. There was a strong wind blowing, aligned with these switchbacks, so almost exactly half the time the wind was at your back – tremendous – or in your face – terrible. But this was hallowed ground for me, as I had been on the upper parts twice during ski tours of Mont Blanc with SG and DC, and it was fun to remember snowy terrain, as it was now presented to me, without the snow.

Encouragement for an earlier rider.

The col was magnificent, magical – it always is – but the wind was blowing straight out of the north, so I did not linger. The descent probably represented the nadir of physical experiences during the whole trip: just as my sunny descent finally got me out of the wind, I lost the sun entirely behind the mountains, and had to glide through unrelenting hairpins, and my cold extremities gradually became cold entireties. Eventually the mountain path merges with the highway that comes out of the tunnel, and is protected by a long avalanche covering. This means (I am guessing) 8km further of descent, in the shade, with no hope of stopping, because there was no verge, and trucks and cars continued to drive me relentlessly forwards.

On the Col du Grand Saint Bernard.

Eventually, I emerged from the tunnel and into the sunshine, and stopped to read the butcher’s bill: although I was trembling uncontrollably, amazingly, no permanent frozen damage done, and I was able to continue a high-speed descent to Martigny, which provided warmth and renewed energy. Martigny is the lowest point (in terms of elevation) in the whole trip.

The climb to the col du Florclaz went slower than I had hoped: I was tired. The day had already been long, and I think the stress of the cold had taken quite a bit out of me. It was good to finally top out.

On the Col des Montets.

That fine descent recharged batteries, and by the time I hit the Swiss-French border, where the climb was to recommence, I was energised. The col des Montets passed easily, and it was a quick schuss from there to Argentière (the scene of the start of so many Haute Route adventures), and then on to Chamonix by about 16:00.

Why must cycling clothes always be so ridiculous? (Sorry, Matt!)

Unlike Saint-Rhémy, there is always space somewhere in Chamonix, and I found a central hotel (I was too tired to venture out of town to find some place cheaper). In Cham I made my normal tour — Snell’s, Patagonia — and then did my postcard duty (while re-hydrating with a couple of beers) in the Irish pub. Dinner in the first restaurant that would have me. I have noticed when you are tired, you are not very picky. In bed by 20:00. Snoring prodigiously, no doubt, by 20:01.

Day 2 Route

Day 3: A Road to Nowhere; More Cold; More Warmth; Too Fast; Home

Again, I wanted to be away by first light, which meant skipping the breakfast provided by the hotel. On the way out of Chamonix, I had flashbacks to the 6 or 7 trail-running Tour du Mont Blanc I had done, as the first few kilometres were on the same route. The difference was temperature. I was always warm running; on the bike I was freezing.

Early morning cold in Chamonix.

At the hotel they had advised me that indeed I could ride my bike down the main road out of Chamonix all the way to Saint Gervais. What they didn’t tell me – because they could not have known – was that the road no longer existed.

The road is a dual-carriageway both ways; rising to Chamonix, it sits on solid ground; but descending from Chamonix, it is a raised highway, several kilometres of which is bridge. As I descended, there were lots of diversion and “men working” signs. Eventually, I got to a point where my dual lane was reduced to one, and then passed over to the left had side, where traffic was passing in both directions, in just two lanes, separated only by cones. It would have been suicide (not to mention probably illegal) to continue, so, foolish optimist that I am, I crossed over the barrier to my right, and proceeded down the closed road that should have made up the route I had planned.

Yes, there were “road closed” signs everywhere. But over the years I have noticed that when they close a road in France, they don’t always definitively mean “Closed”. Agreed, it is officially closed, but sometimes the barriers are flimsy, and those barriers send out a “closed, but not really” message, which the initiated know how to read, and ignore. This is what I thought I saw, so I continued down and onwards, in the hopes that the road was closed but would still pass. Wrong.

Eventually I got to some really serious barriers, where a group of men were milling about, dressed in dayglow vests. I made a kind of supplicant gesture, hoping they would allow me to pass.

“No”.

“But I am just a guy on bike”.

“You don’t understand; it is not that we wouldn’t if we could, but the bridge doesn’t exist any longer; we knocked it down, yesterday”.

And so it was: my planned route didn’t even exist. I literally was on the road to nowhere.

Not only was I crestfallen, I was effectively lost: certainly I knew where I was at that moment, but had no idea how to get to where I wanted to go. The workers must have been both local and perceptive (let’s add a third characteristic, cyclo-savvy), because they immediately saw my dilemma, and started discussing my options amongst themselves. And they quite ignored me in doing so. Eventually, there was a great nodding of heads, and one of the group explained to me, at length, in great detail, and at a speed I barely understood, the best way for a cyclist to get from there to Saint Gervais, without killing himself.

He was perceptive enough to realise I had no hope of holding such detailed directions in my head, so said, “follow me”.

He got in one of the vans, and headed off. I followed as best I could – he was moving at pace — down a narrow route to a small tunnel under the main road, then up through les Houches to the far end of the town, and a narrow but paved forest road. He then distilled his previous thousand-word set of directions into a just four: “From here, keep going.”

The road was paved, and although not it good shape, it passed well. For a while I was in dense forest on a relatively flat bit, where I saw lots of animals. That broke suddenly into a precipitous chain of switchbacks, at first in forest, then in village, and finally back to the main road I had originally hoped to be on. It was a fun descent, but it was debilitatingly cold.

There was a climb to Saint Gervais, but somehow it didn’t warm me. The road was narrow and winding, there was plenty of traffic, concentration was required, and apart from steering the bike and turning the legs, there was little to do but be reminded of how cold I was.

When I got to Saint Gervais, it was clear I was still a good hour away from the sunshine, and would have to climb to get to it. Was this the emotional, as opposed to physiological nadir of the trip? Very possibly. But just as I got off my bike in front of a boulangerie, intent on buying a sandwich and warming up, my phone pinged with a text message from a friend.

In fact it was not much of a message, something like “I hope you have a good day…”, but it came from someone I care about a great deal, and arrived at just the right moment. Off the bike, into the boulangerie, a sandwich, a coffee (ordered as “…the strongest, biggest, hottest coffee you’ve got…” — and it was), and 30 minutes later I emerged re-charged, re-inspired, and ready for the climb to les Saisies.

When I finally hit the sunshine, I was not far from Mejève, and warmed up very quickly after that.

By this time, I think I was cycling in zombie-mode. It was nice to be in the warmth and in the sunshine, and the terrain, although not spectacular, was agreeable. But by then, I had spent the better part of two and a half days just spinning my legs about 90% of the time (the other 10% being descent). Climbing is something you want to do in as regular a way as possible: find your preferred cadence and force, and grind away at it. It is monotonous; it is hypnotic; it can be calming, but after two and a half days, it just seems dull.

Col des Saisies

But what goes up must come down. The descent from the col du Saisies was anything but monotonous or zombie-like: a quick course of tight switchbacks gave way to longer straights where I was hitting some pretty high speeds. The road surface was highly varied, so at times, I was thinking that all that tooth-rattling was going to necessitate a call to AJ, my dentist sister-in-law.

Besides the dental considerations, one other thing started gnawing away in my mind: the descent was too long. After a while I passed through what I thought was my target altitude where I should start climbing again, but then kept on going. Allowing for slight miscalculations, I fibbed to myself that everything was okay, but eventually, one of two conclusions was forced upon me: either I was hopelessly lost, or I had somehow miscalculated the altitude of Beaufort.

In the end, the latter turned out to be the case. I am not sure how, but in my mind I had Beaufort to be at 1,400m altitude; the reality is closer to 700m. Although that additional 700m had made up a delicious descent, it meant there were 700 more metres of climb than I had planned, before I hit the final col, the Cormet de Roselend. What I had imagined would be 500m of climb would in fact be 1200m.

I was not happy.

But it was beautifully warm in Beaufort, not far off midday, and I stopped at an inviting café in the town square, where I demolished a ham sandwich (not as good as the first day’s, but I expect I’ll never see another sandwich like that, and will have to just get over it) and strong coffee. Replenished, I headed off again.

The climb from Beaufort starts in a narrow valley that is heavily wooded. Although there is very little other than pine trees to see, the tightness of the valley means the switchbacks are sporadic and unpredictable. Eventually the valley broadens, the trees relent, the road straightens just a bit, and the sky opens above. It was warm, but not hot, and I knew that despite my previous miscalculations, I was certainly on the last climb of the whole trip.

Mentally, everything was transformed: I was on my victory lap.

I gobbled up bornes routières (the archetypal kilometre markers at the verge of all major French roads) at a climbing pace I had not seen since early the first day. The artificial lake sustained by a huge Electricity de France dam towards the top arrives before the cormet, and is spectacular. When you first see it from the Beaufort side, there is a long, straight, slight descent, and so you can stop pedalling, just enjoy the view, and still make good time. And the view was spectacular.

The lake just below the Cormet de Roselend.

Thereafter, the wind seemed at my back (figuratively, anyway), and the last climb to the col passed quickly. I agreed with some other cyclists to take photos of each other in front of the kern that marks the Cormet de Roselend. It was warm, sunny, barely a cloud in the sky, and I was keen on a celebratory, 20-kilometre, high-speed descent into Bourg Saint Maurice.

On the Cormet.

Then the wind truly was at my back. The first part of the descent is remarkably straight for a mountain road. There are bends and even switchbacks, of course, but I’d guess you could do the first 9km or so, without ever hitting a turn that demanded sub 40km/hr speeds.

So I hit over 75km/hr on the first long stretch, which is easily a personal best for me. Like so many things in life, it scared me, but I loved it. Eventually the straight-ish bits gave way to a series of very tight and narrow switchbacks, and I lost the sun. It wasn’t until I was a few kilometres from Bourg that it re-emerged, with perfect timing, because I was getting cold.

At Bourg I stopped at a few places where I knew friends would be working, and received (participated in?) some of the nicest hugs I have had since covid. I thought of stopping for a beer at le Tonneau, a very central bar with a fine terrace on the main street of Bourg, but forewent that.

It was time to go home.

And so I did.

Réboussoléd

Day 3 Route.