Not The Cruellest Month

According to T.S. Eliot, April is the cruellest month.

Well, he may have been a great poet, but Eliot was a rotten meteorologist.

A lot of nice things happen in April, at least where I live (France, and hence the northern hemisphere, when April is in the spring), and it has always seemed a very forward, uplifting time to me.

If I had to nominate the most difficult month – and I still wouldn’t call it cruel – I would have said November.

Compare the two: My Mom was born in April. Likewise VC, SD, JL, AM and many other of my friends. That is hardly meteorology. But still, so many nice people, what’s not to like? April, and the period surrounding it, is a time for hopeful anticipation, because it provides the transition from cold winter, through spring and into warm summer.

November is the inversion of all that (although I do know some nice people who were born in November). It is too late for Indian Summer. Any colourful leaves have long since fallen. The clear, vibrant cold days of full-blown winter have not yet arrived. Any precipitation falls only as rain.

Around my house, nothing ever really dries out properly. The bathroom is chilly, the house, in general, difficult to heat. It is the month where the sun struggles most. When streams and rivers are most likely to overflow their banks.

For this and other reasons, I was feeling rebellious this November, and decided to take a quick break in Paris, a city I hadn’t visited in a very long time.

To begin with, I resolved to remain light-on-my feet and book at short notice when the first period of four to five clear days was forecast. But as the month wore on – that November weather again — it was obvious those good days were unlikely to happen, and in a “to hell with it” moment late one Thursday afternoon, booked the whole thing, transport, hotel, kennel for the dog and all, and at 06:00 on the morning of the next day, was shaking the rain off my shoulders while standing in a train that was just pulling out of the station at Aime. I felt a bit like Bogie, in the train scene from Casablanca, but somehow in reverse. Unlike him, I wasn’t leaving Paris. That train would take me to it.

And I wasn’t heartbroken.

To Paris.

To the City of Light.

Ways of Seeing

Part of the reason for going to Paris was that during the previous trip to the UK in October, I had picked up a book in Cambridge, a new biography of Monet by Jackie Wullschläger, called Monet: The Restless Vision, and started reading it right away.

On the penultimate day of that trip, I was in London, an appointment was cancelled, so I dove into the National Gallery, as my research had indicated some of the paintings mentioned in the book were actually housed there.

This visit was a revelation.

I have been to lots of museums and galleries in my day, but – surprisingly – I have never gone to one to see specific works of art, for which I knew a bit of the back story.

So it was a revelation.

The paintings, set in broader context, seemed much more alive, as if animated; you knew what the artist was trying to achieve, or what was happening in his/her life. So rather than just seeming like an object in front of you, a painting became part of a developing timeline, set in the midst of someone’s struggles, a brief moment of their joy or a longer slog through their depression.

If that strikes you as me showing a stunning lack of experience, I can only say guilty as charged. It amazed me that I had never done this kind of thing before. Galleries yes; research beforehand, no.

A Wide-Eyed Kid

In Paris, I was a wide-eyed kid in the museums, and probably would really have embarrassed anyone who knew anything at all about art. (You know who you are.)

For example, some very fundamental part of me really wasn’t at all ready for the 5th floor of the Musée d’Orsay. As the trip was booked at the last minute, there was no time to do any research regarding what might be there. From the biography, I knew there were plenty of Monets, as well as many of the other Impressionists, but I didn’t know exactly which. But some, which I had read about, were bound to be in that museum.

As soon as I was through the turnstiles, I was up to the 5th (“straight to the 5th”, this much advice I did know), and it was almost devoid of people to begin with. I had already decided I’d dash around the floor in reconnoiter-mode once, note 5 – 10 paintings I wanted to spend time with, then double back and spend the time with them.

I just wasn’t ready for the choice being so overwhelming. I wasn’t necessarily interested in famous paintings, but there are just so many famous paintings up there. For a second just choosing which seemed like an absurdly ambitious task. But then I returned to first principles, and remembered I wasn’t there to see famous paintings, but paintings I wanted to see, because of the biography. And paintings I didn’t know I wanted to see, but which caught my eye during the first quick dash ‘round. In the end, I chose more like 15 than 5, and whittling them down was difficult but doable.

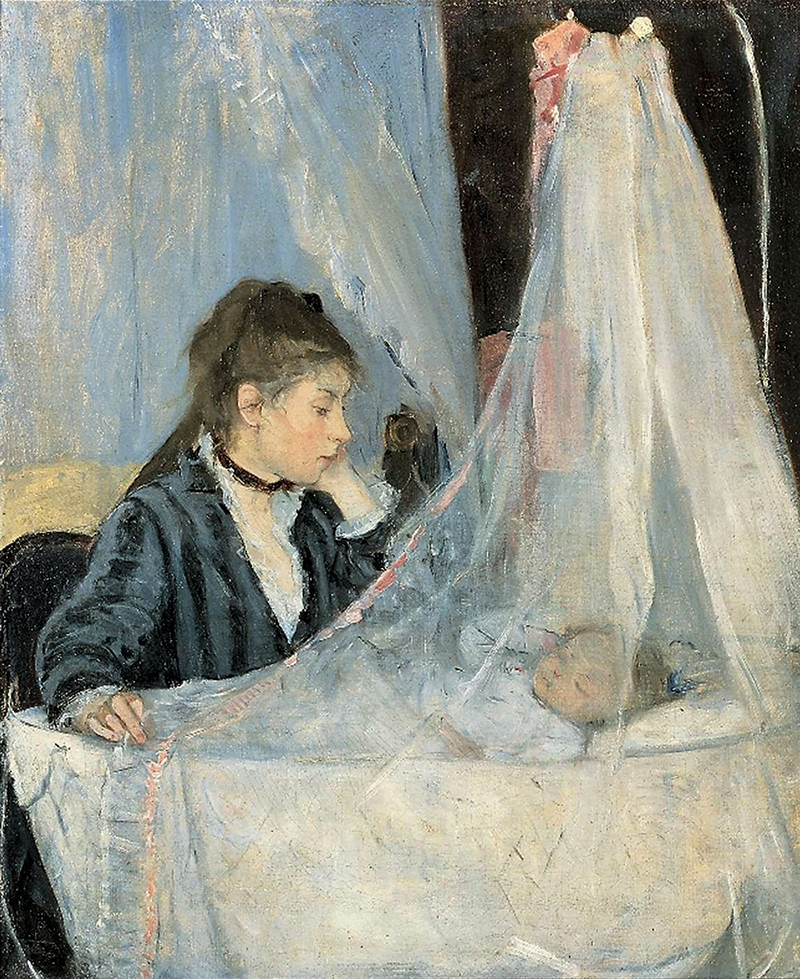

What was really amazing for me was how many times during a longish viewing (say 10 – 15 minutes) of a canvas, new things suddenly popped into view. But I mean “things” in a special way, not a tree, a boat or a person, but sometimes something like a colour that only seems to appear once in the whole work, or how he/she paints water or the folds of tissues, a bit of the painting that seems unfinished, or when there are not too many people viewing, getting in really close to see how she/he achieves things. (Sad to say, the only “she” I saw was Morisot.)

A Morisot

You’re going to laugh at me, but I’ve never done that in an art gallery before. In the past, I’d wander around, look, read the note, look again, then move on. Spending a good hefty bit of time with each was really a new and wonderful experience for me.

Ways of Not Seeing

I was really surprised at the number of people — probably not far off half — who would just go up to a painting, take a photo and then move on. They never stopped to look. Click-go, click-go, click-go…. I was dumbfounded by this. Why pay the admission? You can have all the photos you want from the internet.

A subspecies of this group could be called “the serial poser”: people who’d go up to a painting and take a selfie with the painting and themselves in the frame. Then rapidly move to the next. I noted these people also very rarely spent time looking at the paintings themselves. Pose-click-move on. I wondered if, in another life, they would return as big game hunters. Never mind the beauty of the animals, just bag them and stuff the heads for the den wall.

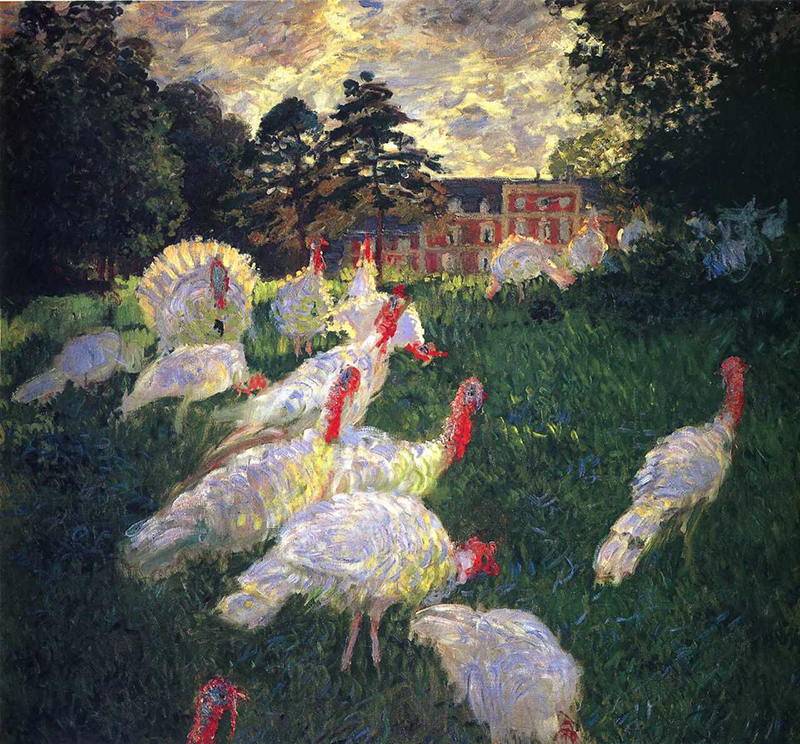

The next curious experience came when I was standing in front of a Monet that I had not really known before, but which was described at length in the biography and had caught my eye during my first pass. It is an unusual painting, as the view is dominated by a flock of white turkeys, on the ground, with a manor house behind. Close up, it was quite stunning. And I was not the only one who thought so.

For a brief moment I was the only one looking at it. But then suddenly a man, perhaps my age, came straight up to me, grabbed my forearm with both his hands, squeezed, and started enthusing, at great speed (not to mention embarrassing volume), in a passionate voice.

At first he stumbled for words, like an inexperienced driver trying to get a clapped-out car started:

“It is… it is….. it is……..”

But he eventually got the motor going, and shifted into a high-rev first.

He used just about every superlative that I knew in the French language, and a fair number I didn’t know.

Then he changed gears.

He didn’t believe such a painting could exist. He didn’t know humans were capable of such things. Were humans capable of such things? It was wonderful. Was it real?! Did I believe it was real?

All this while I was silent. Why put any effort into a conversation when someone seems so content to supply both halves.

One more shift and he maxed out:

“I’m thinking Munch, 1893, but that would have been 20 years later! Impossible!! Quite impossible!!! I am thinking Schlele, 1910, I’m thinking Heckel, 1915, I’m thinking….”

And indeed, he was thinking a lot of artists I’d never heard of before, and a lot of years I failed to know the significance of.

For my part, I almost got the giggles, as while he was rattling off all these artists and years, it came to me that a good response would be, “I’m thinking the Leafs, 1967” (the last time the Toronto Maple Leafs won ice hockey’s Stanley Cup).

I supressed this, but he finally ran out of gas, coasted to a halt, looked quietly for a few moments longer. And moved on.

I’m thinking relief, 2023.

Ways of Meeting People

But please don’t think I disliked all my fellow gallery-mates. Standing in the pre-opening queue of a museum, in the rain, first thing in the morning, is a great way to meet very fine people. As I had arranged the trip at the last minute, all the pre-booking tickets had sold out, so the only course of action was to get to a gallery well before it opened in the morning, and stand in the queue.

First day, in front of the d’Orsay, I met a couple from Lebanon. We had a great discussion, swapping facts about our native lands (I had no idea Kahlil Gibran was from Lebanon), travel stories, what we wanted to see in the gallery, stray observations on Paris or just life.

Second day in front of the d’Orsay I met a couple from Caen and a woman from Toulouse. We spoke as one group together, and chuckled to think that we lived about as far away from each other as we possibly could and still be in France. The biggest possible French travel triangle. We shared more very pleasant “been there, done that” stories. Tips for where to travel next. The Caen couple had visited Monet’s garden at Giverny a few years before in May, and truly seemed at a joint loss for words to describe how beautiful it is at that time of year.

I had managed to pre-book for the Orangerie, and so was straight in at my appointed hour, and kind of missed the queuing. I didn’t meet any people there. It seemed a loss…

In front of the Louvre, a Korean guy and I fell into giggles (or as close as I think he ever gets to them, he was otherwise quite shy) because we simply couldn’t understand each others’ English accents. Lot’s of recognisable words, but not enough to transmit meaning. It seemed enough just to laugh at that.

The other person I spoke to in the queue turned out to be Russian. You could see that, given the current political situation, she was a little bit nervous and embarrassed as she confessed her nationality (she probably knew the question was coming, as she would have overheard the Korean and me talking); and it was clear she felt relieved when the fact passed though the conversation without comment or ill-effect.

She was a serial traveller, she seemed to have been everywhere, but everywhere, and when I asked her for her favourite city, she just rolled her eyes into the back of her head, as if at once to express being radically spoiled for choice, and also being confronted with a somewhat stupid, impossible-to-answer question. However she didn’t make me feel dumb for my dumb question; she just began enthusing her way through her top ten.

But then the line finally began to move, we passed inside and through separate turnstiles, and never saw each other again. It reminded me very much of a beautiful passage by Colin Thubron, which I actually have managed to locate. It goes like this…

Mushroom Hunting in Russia

To the Russian the wild mushroom has a peculiar mystique, and these expeditions lie somewhere between sport and ritual. They mingle the country-love of an English blackberry hunt with the delicate discrimination of the blossom-viewing Japanese. If Russia’s national tree is the silver birch, then her national plant is this magic fungus, burgeoning in the forest shadows… Russian mushrooms

“Mushroom-hunting… I wish I could express it to you.” Volodya’s face became filled with this obscure national excitement. “It’s like this. You get into the forests and you know instinctively if the conditions are right for them. You can sense it. It gives you a strange thrill. Perhaps the grass is growing at the right thickness, or there’s the right amount of sun. You can even smell them. You know that here there’ll be mushrooms ” – he spoke the word “mushrooms ” in a priestly hush – “so you go forward in the shadows, or in a light clearing perhaps, and there they are, under the birches!” He reached out in tender abstraction and plucked a ghostly handful from the air. “Have you ever sniffed mushrooms? The poisonous ones smell bitter, but the good ones – you’ll remember that fragrance for ever!”

He went on to talk about the different kinds and qualities of mushroom, and how they grew and where to find them – delicate white mushrooms with umbrellaed hats, which bred in the pine forests red, strong-tasting birch-mushrooms with whitish stems and feverish black specks; the yellow “little foxes “, which grew in huddles all together: and the sticky, dark-tipped mushroom called “butter-covered “, delicate and sweet. Then there was the apyata which multiplied on shrubs – “you can pick a whole bough of them!” – and at last, in late autumn, came a beautiful green-capped mushroom which it was sacrilege to fry. All these mushrooms, he said, might be boiled in salt and pepper, laced with garlic and onions, and the red ones fried in butter and cut into bits until they appeared to have shrunk into nothing, then gobbled down with vodka all winter.

We set on the verge for a little longer, talking of disconnected things. He was going to Brest, and I to Smolensk, and it was futile to pretend that we would ever meet again. This evanescence haunted all my friendships here. Their intimacy was a momentary triumph over the prejudice and fear which had warped us all our lives; but it could never be repeated.

Volodya clasped my hand in parting, and suddenly said: “Isn’t it all ridiculous – I mean propaganda, war. Really I don’t understand.” He stared at where we’d been sitting – an orphaned circle of crushed grass. “If only I were head of the Politburo, and you were President of America, we’d sign eternal peace at once ” – he smiled sadly – “and go mushroom-picking together!”

I never again equated the Russian system with the Russian people.

Seeing the Words but Not the Meaning – Back to the d’Orsay

I mentioned somewhere above that I had a second go in the queue in front of the Musée d’Orsay. I had better explain.

On that first day, after about two and a half hours, I found myself standing in front of a painting, looking at it, and not really taking it in at all. It felt exactly like the same sensation we have all had while reading when tired: you get to the bottom of a page, you know you have seen all the words, but you know no meaning has entered your head.

Trying to persist somehow never works for me in a reading situation, and I knew it would be futile to try with paintings: best just to give up.

However, it is much easier to put down a book and pick it up later when you are refreshed, than it is to leave an art gallery before you feel you’ve exhausted it, while knowing that it has exhausted you. To do the d’Orsay again the next day, I’d have to sacrifice something else I’d wanted to see, get up early, walk all that distance (this is Paris, I sure wasn’t going to take the metro), stand in the queue again, and pay the admission anew.

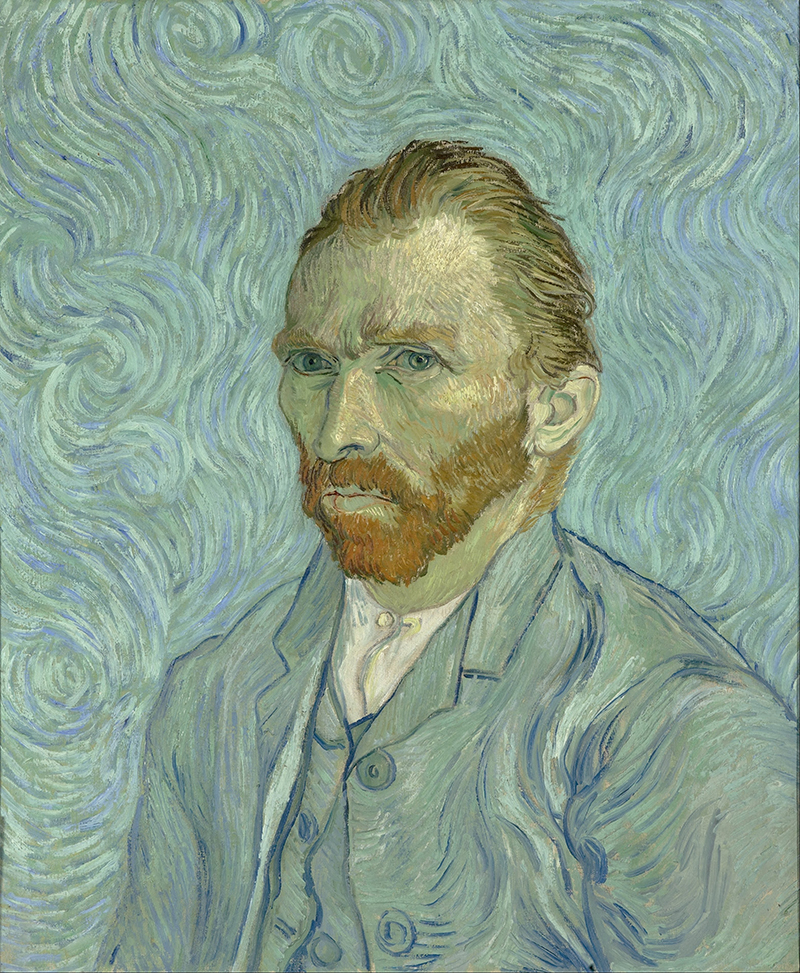

But I knew it would be worth it: there was a special exhibition of Van Gogh, concentrating on the last two months of his life. It was not to be missed, and I wanted to do it with fresh eyes.

So, next day, it was back to the Musée d’Orsay, in the queue, about 45 minutes before it opened.

Everything Stops

When I first quickly read the description of the exhibition, the text was in French, and I simply misread a key word: I went into the exhibition thinking it focused on the last two years of Van Gogh’s life. Re-reading, I realised it was his last two months, not years. That quite surprised me, and I immediately thought it was going to be a pretty small exhibition. How many major paintings can an artist do in about 60 days?

For Van Gogh, the answer is quite amazing: during this period, he produced 74 paintings and 33 sketches, according to the exhibition documentation; and many of those, as the prospectus doesn’t fail to mention, are iconic. The exhibition had about 40 of those paintings, and 20 sketches.

I have now had maybe three attempts to write about that experience in a bit of detail, and it has defeated me. At a loss for words directly, instead, I am going to try to approach it obliquely.

First, they don’t pull their punches. This was the first thing I saw when I entered the exhibit:

Thereafter, the progression is approximately historic: early paintings first, final paintings last.

There is an old passage from Kurt Vonnegut, writing in the 1970’s, and it is now too politically incorrect to quote in full.[1] But it ends pointedly with the phrase…

“….everything stops…”

I am not sure why exactly, but being in the Van Gogh exhibition reminded me of that quote.

Does this need saying:

The paintings all seemed impassioned, the brushstrokes some paradoxical combination of hurried yet precise, dashed off yet spot on, feverish sometimes; one imagines him working very quickly, one brilliant canvas after another, day after day, better and better, faster and faster…

And then one day he is no longer there…

Everything stops.

Failure, Then Victory, in Front of the Winged Victory

I walked almost everywhere, popped into strange shops and cafés, caught glimpses of all the obvious choices like the Eiffel Tower and the Arc du Triomphe.

One surprise: the Apple Store on the Champs-Elysées is truly palatial, in all senses of the word. I had not planned on going in, but when I passed it, it was too beautiful to miss. Yes, yes, it is a shop, but the interior is fantastic, they have preserved it lovingly, it goes up about 5 levels, and you are encouraged to wander ’round like it were a national monument. I suppose it is…

But let’s finish with a vignette from the Louvre. The very first time I was ever there (some 45 years ago?) I was really taken by the Greek statue, The Winged Victory of Samothrace. Then, I had never even heard of it, and stumbled upon it accidentally (or not – it is hard to miss, as it is placed right in the middle of the main staircase of the old museum).

Approximately 2,200 years old, larger than life (assuming the Greeks imagined their gods to be human-sized), headless, armless, one broken wing: a cynic would say it was pretty beat up. But it is just amazing, broken in the most exquisite manor. The missing parts draw you in, engage you, you flesh them out, you imagine what it might have been like in its perfection.

And then you prefer it as it is now. A battered child of history.

My problem was, all these years, I have never been sure how to pronounce the name Samothrace. I have had my own way of saying it, but was pretty sure this was wrong, and never had the presence of mind, in front of someone who might know, to ask.

This time around, I spent a good long period of time, viewing the statue from different angles, and then spied two museum employees chatting to each other. My chance to get the answer from experts.

I went up to them, asked if I could ask a question, then asked it: how do you pronounce it?

They both rolled their eyes, then answered.

Simultaneously.

And differently.

They weren’t in agreement themselves of the pronunciation either.

I went back to appreciating the statue, thinking I suppose it is not such a bad thing to pronounce its name in my own way.

It truly is an amazing work. After a while, looking at it, you realise she is not standing. She is not walking. She is landing: the sculpture captures the moment, just as her right foot is touching down on the ground.

She is winged, after all.

A group of young girls, mid-teens probably, came nearby. They were laughing, making a bit of pleasant noise, talking animatedly, in a language I didn’t recognize. So I asked.

“Where are you from?”

“Greece!”

The exclamation mark was very definitely a part of their response.

“Fantastic! Help me. How do you pronounce it?”. I gestured at the monolith.

They seemed proud of the statue, effectively their statue (indeed, the Greek government wants it back, although it notionally belongs to the Louvre), and said the name in unison.

Loudly and identically.

“Samothrace!!”

I wandered back to the two museum employees. They eyed me suspiciously, afraid I was going to ask another embarrassing question. I pointed out the group of girls, and for a moment I think the museum people thought I was going to complain about the noise they were making.

“They’re from Greece.” I said.

Quizzical looks.

“I asked them. It’s pronounced Samothrace!!”

Smiles. All round.

The Greek goddess of victory had landed. In the City of Light.

[1] To be fair to Vonnegut, I think it is clear from the context that he is not expressing his own opinion in this quote; the words come from a misogynistic character he has created, one he is not in sympathy with.