In 1826, a year before his death, Ludwig van Beethoven completed his string quartet number 14 in C# minor, opus 131.

Although it was not well received by the general public upon its first performance, a rather large number of quite significant musicians seem to have thought highly of it in their time.

Beethoven String Quartet 14, Opus 131, first movement

When Schubert first heard the piece, he is reported to have said, “After this, what is left for us to write?” And as he lay dying, a year after Beethoven’s own death, Schubert asked for it to be played, and his closest friends obliged him. It was very possibly the last piece of music Schubert heard in his life.

Let us pause there for just a moment. Imagine that situation: recorded music does not yet exist; to hear music, you need musicians. You are Schubert, you know you are dying, you have dedicated your whole life to music, and you want to hear just one last piece. But you cannot just flip a switch to do it. So you must choose carefully, and be realistic. Your options are very constrained by the number of musicians you can assemble, at short notice, in your small death chamber. There isn’t time for rehearsals. A symphony is out of the question. And so he chose a quartet. For him, THE quartet.

Now imagine the musicians who obliged Schubert. All were friends. All knew he was dying. All knew they were fulfilling his last musical request. Imagine yourself, the first violin, picking up your instrument and bow. The two are surrealistically light in your hands. You look at Schubert. You look round the circle of three other musicians. You look them in the eyes; to repeat, in the eyes. And so to begin, you dip your head quickly, and start to play. As it is something of a fugue, you play solo, for a few bars, to the dying Schubert. In their turn, your colleagues join you. Together, you play for Schubert. You play for Beethoven. You play for music itself. And you play Opus 131…

Schubert was not alone in his admiration of the work. Robert Schumann described it (along with opus 127, 130 and 132) as possessing a…

…grandeur of which no words can express. They seem to me to stand…on the extreme boundary of all that has hitherto been attained by human art and imagination.

Wagner wrote extensively about the piece, saying the first movement “…reveals the most melancholy sentiment expressed in music.” Many modern musicologists have followed suite in their enthusiasm.

The list of professional accolades goes on and on. On the basis of this alone, it is clear this work is thought by the many who are experts in such things to have a transcendental, surpassing value. One of the truly great masterpieces of all ages and all human accomplishment, not just in music, but in art more generally, and human endeavour more generally still.

This is a Mona Lisa, a Hamlet, a van Gogh Crows in a Cornfield, a Faust, a Seventh Seal, a Winged Victory of Samothrace, an Iliad, an 18th Sonnet. This is one of the surpassingly brilliant works of art that man has ever known…

What are common people like you and I to make of such a thing? I must admit that in my music collection I have at least 2 copies of Beethoven’s string quartets, and have no doubt played them, many times, as a kind of incidental music, while doing other things. To be sure, I have probably “listened” to Opus 131 a dozen or more times over the past 20 years. That is one of the great advantages and great curses of music: because you can listen to it, and do other things at the same time, you do listen to it and do other things at the same time. But when you do, you are not mindful of its passing.

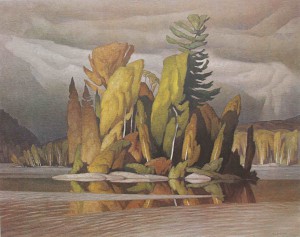

For example, sad to say, but in these dozen or so “hearings” of Opus 131, I never actually noticed that it was a particularly great piece of music. Is this because musical greatness just doesn’t stand out in the same way that greatness in other media does? For example, I only need to glace at A.J. Casson’s “Little Island” to see that something significant is happening:

A.J. Casson – Little Island

And persistent viewing, especially in front of the original in the McMichael Gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario, confirms (for a Canadian, at least) that I am taking in something truly great.

I think part of this special kind of domain blindness does relate to the fact that we can listen to music absent-mindedly. And you might want to argue that you can do the same with visual images. Presumably if I hung Casson’s work in my living room, I very quickly would grow numbed to its greatness. I would see it in the sense that I would perceive that it was there, and would certainly notice immediately if someone stole it. So I can see it, without appreciating it, in the same way I can hear Opus 131, without actually listening to it.

But it seems to me this analogy breaks down rather quickly when you flip the coin and make a conscious effort to appreciate a work, be it a painting or music. I can take any length of time out, any time I want, genuinely to appreciate the painting. Fifteen seconds or 15 minutes both yield a valid experience.

This is less true (almost to the point of being untrue) when it comes to music. Yes, in the modern world we can pop the CD into the stereo, although this is a recent innovation: recall Schubert having to assemble the requisite musicians for his last musical request. But further, music makes its own time demands. Although it is frequently noted that music is timeless in the sense that a performance of it doesn’t persist over time in the same way that a painting or a sculpture does, music does set its own rules regarding time. The whole painting stands before you in the moments you look at it; music, on the other hand, unfolds itself in time, and unless you are prepared to spend the 40 or so minutes required to take in the whole piece, you cannot really have said that you listened to it. A fragment of it, perhaps, but not the whole piece. The painting does not make the same stringent demands on your time.

So I arrive at the central question of this essay: How can someone like me, comparatively unversed in music, aspire to a more qualitative appreciation of a great work of music like Beethoven’s Opus 131?

That is the central question of this series of essays.